This is the last of three book reviews on the One State Solution I started a few weeks ago. I previously reviewed Ian S. Lustick’s Paradigm Lost: from Two-State Solution to One-State Reality, and Omri Boehm’s Haifa Republic: A Democratic Future for Israel. From time to time I will add additional One State reviews.

Jonathan Kuttab has dedicated much of his life to human rights, first as one of the founders of Al-Haq, a Palestinian rights group established in 1979, and also as a co-founder of Nonviolence International in 1989. Kuttab is a Palestinian Christian lawyer who has practiced in Israel, Palestine, and the US and was the head of a legal team that negotiated the 1994 Cairo Agreement between Israel and the PLO. In 1980 Kuttab co-authored a study of Israeli military laws governing the West Bank that had been modified from British Mandate and Jordanian law to apply more draconian control over Palestinians and to “legalize” land theft.

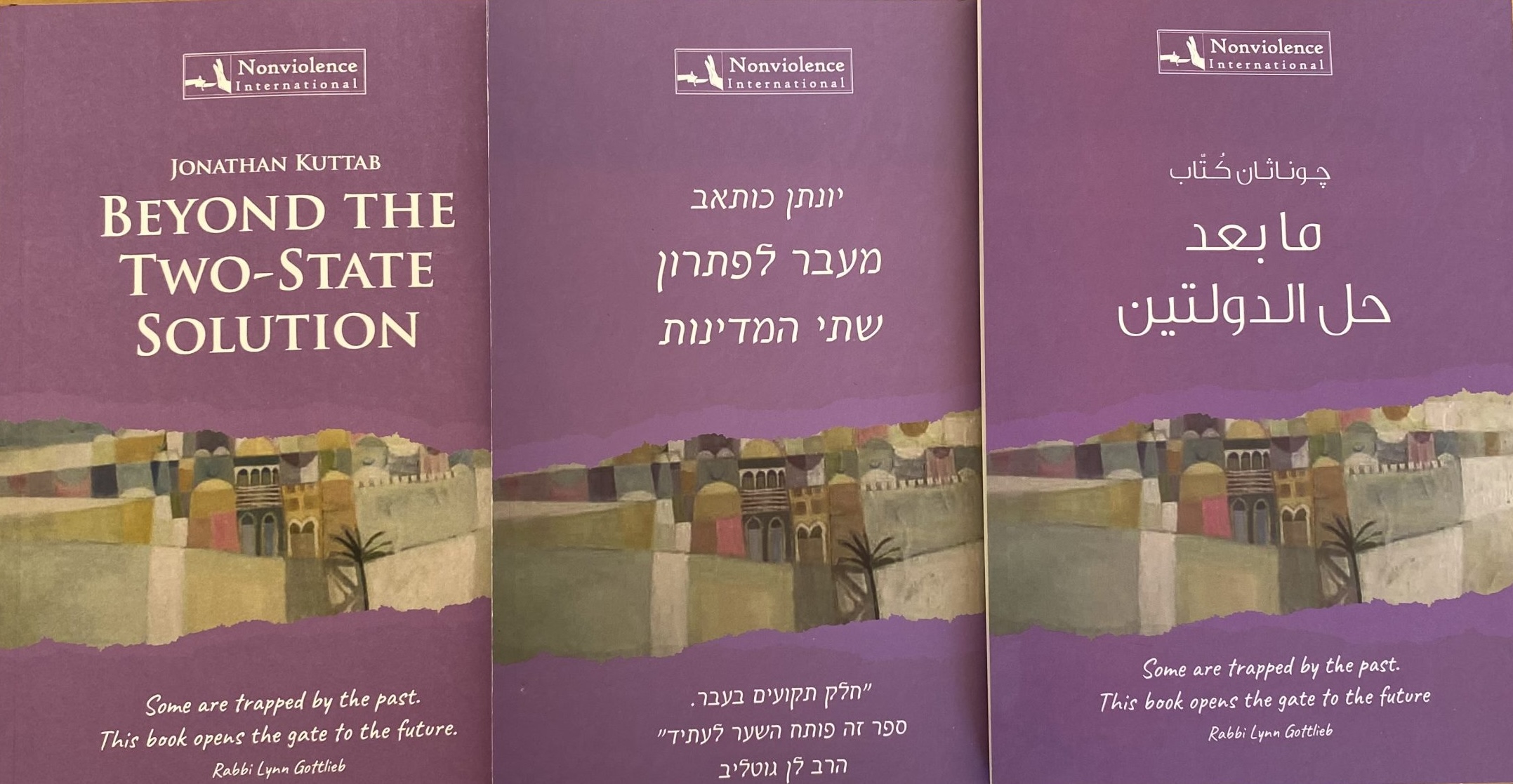

Kuttab, then, is as qualifed as anyone to present a non-violent program for a One State solution in his book “Beyond the Two-State Solution,” available in English, Hebrew, and Arabic print editions and also in electronic format.

Despite his conciliatory tone, Kuttab doesn’t pull any punches. Zionism is a land grab and, following each war and Oslo, Israel always grabbed as much land as it could — finally rendering impossible a Two State solution. Kuttab analyzes the many failed brokered peace agreements and tries to isolate the unresolved sticking points.

Kuttab acknowledges Israel’s extreme preoccupation with security, the status of Jerusalem, the Palestinian right of return, and a difficult-to-imagine reversal of illegal settlements. After looking at all the proposals that bowed to Zionist domination, he eliminates Two States as a workable solution because “the language of the Two State Solution leaves the battling ideologies intact, and only requires a geographic division and spatial limitation on the exercise of each ideology. Chauvinism, racism, discrimination, and inherent problems are all swept under the rug. No real critique of Zionism or Palestinian Nationalism is required, if we accept the language of the Two State Solution.” Kuttab’s rejection of Palestinian nationalism may grate on those who want to discard one nationalism for another.

Kuttab begins by enumerating the “minimum requirements” for Jewish Israelis when entering into a bi-national state: (1) the Jewish Right of Return; (2) Security; (3) a Jewish rhythm of life; (4) Hebrew; (5) the right to live anywhere in Palestine. For Palestinians the list is virtually identical: (1) the right of return for refugees; (2) Democracy; (3) respect for and protection of Arab Identity; (4) Arabic; (5) the right to move about and live anywhere in Palestine. Kuttab sees no pragmatic impediment to a bi-national state and sets about describing how one could be realized, how national and meta-national laws and even a bi-national Supreme Court could protect both peoples with binding judgments instead of hollow actions in toothless international courts.

Kuttab throws out any number of concrete suggestions for structuring a new bi-national state, but these are only useful to illustrate the point that any serious party could come up with plenty of workable ideas. For this reason it’s not worth dissecting Kuttab’s specifics because specifics must be proposed by both parties and negotiated only after both come to terms with the reality that a bi-national state is the only possible option.

Kuttab writes that “Jewish fears need to be addressed forthrightly” (but of course Palestinians have their own well-justified fears). Kuttab demonstrates enormous (disproportionate?) sensitivity to the fears of Jewish Israelis who, even with the most powerful and only nuclear military in the Middle East, habitually reject Palestinian rights because they are perceived to limit Jewish security. So Kuttab suggests writing Jewish supremacy into the new state’s legal system with a Lebanese-style requirement that the head of the new bi-national military always be Jewish, while the head of the national police always be an Arab. As much as I respect what Kuttab is attempting here, it is an odd and lopsided provision that cannot fail to be a show-stopper.

in remaining chapters Kuttab addresses other objections and challenges to his proposals. One is that a bi-national state has never succeeded before. But is that true? Kuttab writes that Lebanon and Yugoslavia may have foundered because of ethnic strife, but Switzerland and Canada are examples of successes of confederation models.

Even if a successful model did not exist, Kuttab writes that the Holy Land is a special case that deserves special effort, and that a resolution of this particular conflict could play an outsized role in resolving other regional and global conflicts.

Kuttab asks rhetorically why Zionists — having “won” — would ever agree to anything limiting their power or supremacy. The quick answer is that Israel’s victory has never been a stable “win” and, in any case, is not sustainable without bottomless aid and diplomatic cover from Western colonial enablers who will eventually tire of subsidizing human rights abuses. And in the long run the injustices perpetrated on Palestinians cannot be ignored forever.

Another objection Kuttab addresses is the argument that the degree of enmity is so great that it can never be surmounted. If this were true then contemporary national alliances of the 21st Century would be impossible — consider Britain and France, the US and Germany, the US and Japan, Germany and Israel. Many of these former bitter enemies became friends within a generation following the end of conflict.

A final argument for pursuing a single state — and against doing nothing — is that, under Zionism, there is no place for minorities. The logic of Zionism requires that minorities (Muslim, Arab, Bedouin, Christian) can never be allowed to become a majority, and which requires that they must either be repressed or eliminated. But this is logic of the 18th and 19th centuries. A multicultural democracy is manifestly superior to endless occupation, war, racist law, and the perversion of democracy.

Kuttab never says so explicitly, but ultimately Israelis will recognize that Zionism is incompatible with democracy. As fantastical as such a prediction sounds in the middle of Israel’s most genocidal war to-date, Israelis will eventually admit that Zionism did its job of saving millions of Jews but it is now time to abandon it, just as Palestinians will have to abandon their own nationalist aspirations — that is, if a bi-national state is ever to take root.

Kuttab’s final chapter is a discussion of what one might call the “attitude adjustments” necessary to make a bi-national state possible. Kuttab, as a proponent of non-violence, rejects armed resistance for both pragmatic and moral reasons (to give you a sense of where he comes from, he’s on the board of a Christian Bible college). Before the two peoples can ever start to build a shared state, settlement will have to stop. Israeli’s aren’t going away, and not all settlers are extremists, Kuttab writes. Likewise, Hamas isn’t going away and (contrary to the propaganda) many of their members are moderates. In any case, Hamas will have to be part of any One State solution.

Palestinians have rights and agency. Thus, truly democratic elections in Palestine — not a US-Israeli-appointed regime – would have to precede any sort of political realignment in order to obtain Palestinian agreement. Collective punishment has to stop immediately. Gratuitous repression and domination for domination’s sake would have to end. “Administrative detentions” and many other Israeli excesses and daily insults would have to cease before Palestinians could enter into a new state with Israelis. Terror attacks (from both sides) and Israeli military incursions would need to stop immediately.

Jonathan Kuttab joins many other One-Staters who have reached the same conclusion — that Two States are now an impossibility and, even if feasible, would only defer and compound the conflict. As unimaginable as One State is now, it is the best and only hope for two peoples sharing one land.

Comments are closed.