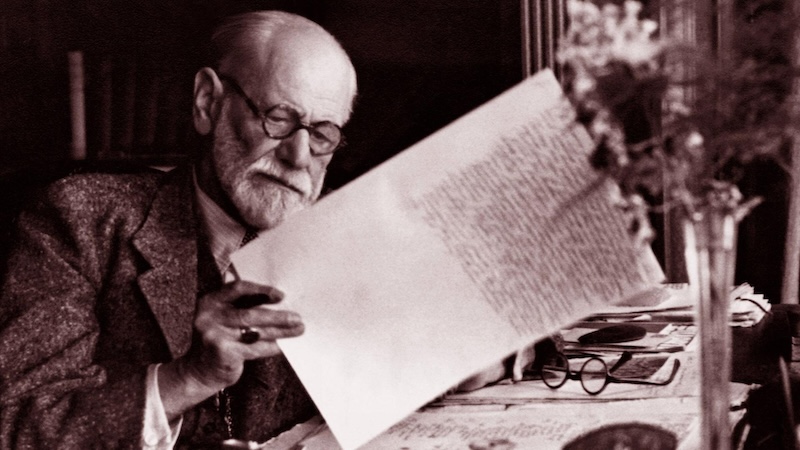

For some time the title of this blog has been Civilization and its Discontents, the English title of a monograph published by Sigmund Freud in 1930, shortly before Nazism finally took power. In times like that — remarkably similar to times like this — people naturally question why they live in societies, particularly those breaking down, and what their relationship to those societies should be.

The German title of the monograph is Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, where Unbehagen conveys uneasiness instead of simply discontent. In 1930 the world was changing — not in a good way — and there was a sense of dark, imminent social and political changes, much like birds know a storm is brewing.

As with much of Freud’s other work, Unbehagen dealt with id, ego, sex, religion and morality. Freud pointed out that societies offer their own pleasures while demanding of their members normative behavior (prohibiting even victimless, non-criminal behavior) that denies primal instincts that could undermine the presuppositions of social institutions. Today’s MAGA fundamentalists, with their insistence on hetero-normative sex and a hypocritical moral code from which their own leaders are always excused, have nothing on Weimar prudery or any of the world societies Freud examined.

Freud identifies “three sources from which our suffering comes: (1) the superior power of nature, (2) the feebleness of our own bodies and (3) the inadequacy of the regulations which adjust the mutual relationships of human beings in the family, the state and society.” There is not much to be done about the first two, but the third (family, state, and society) is the subject of his monograph.

For Freud, religion was just one of a number of palliatives to reduce human suffering — something “so patently infantile, so foreign to reality, that to anyone with a friendly attitude to humanity it is painful to think that the great majority of mortals will never be able to rise above this view of life.” If societies stifled human desire, religion was even more pernicious:

“Religion restricts this play of choice and adaptation, since it imposes equally on everyone its own path to the acquisition of happiness and protection from suffering. Its technique consists in depressing the value of life and distorting the picture of the real world in a delusional manner — which presupposes an intimidation of the intelligence. At this price, by forcibly fixing them in a state of psychical infantilism and by drawing them into a mass-delusion, religion succeeds in sparing many people an individual neurosis. But hardly anything more.”

Besides religion, other mechanisms of “displacements of libido” (sublimation, for example) distract humans suffering from deprivation and want. The ego, Freud says, can elevate human consciousness to spheres of imagination (art, science) or fantasy (religion, psychosis, narcissism) — but according to Freud’s “pleasure principle” a person’s underlying primal needs must always be met directly. Those needs — and the aforementioned tensions between individual, family, society, and the state — form the basis of our unease or discontent:

“[…] what we call our civilization is largely responsible for our misery, and that we should be much happier if we gave it up and returned to primitive conditions. […] How has it happened that so many people have come to take up this strange altitude of hostility to civilization? I believe that the basis of it was a deep and long-standing dissatisfaction with the then existing state of civilization and that on that basis a condemnation of it was built up, occasioned by certain specific historical events. […] There is also an added factor of disappointment. During the last few generations mankind has made an extraordinary advance in the natural sciences and in their technical application and has established his control over nature in a way never before imagined. […] But […] this newly-won power over space and time, this subjugation of the forces of nature, which is the fulfillment of a longing that goes back thousands of years, has not increased the amount of pleasurable satisfaction which they may expect from life and has not made them feel happier. […] What is the use of reducing infantile mortality when it is precisely that reduction which imposes the greatest restraint on us in the begetting of children, so that, taken all round, we nevertheless rear no more children than in the days before the reign of hygiene, while at the same time we have created difficult conditions for our sexual life in marriage, and have probably worked against the beneficial effects of natural selection? And, finally, what good to us is a long life if it is difficult and barren of joys, and if it is so full of misery that we can only welcome death as a deliverer?”

Comments are closed.