A recent article by Jennette Barnes in the Standard Times reports that Bristol County Sheriff Tom Hodgson is refusing to participate in a pilot Department of Corrections medically-assisted [opioid] treatment (MAT) program that five other Massachusetts sheriffs have already signed on to. The program would offer methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone to people leaving prison within 30 days. As usual, the sheriff ignores best practices by denying these treatments. Hodgson’s denial of opioid treatment to prisoners is going to get people killed — if it hasn’t already.

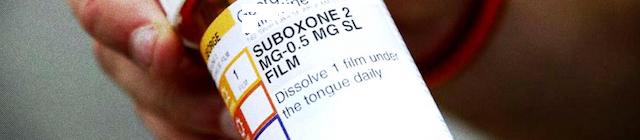

Currently, prisoners at the Bristol County House of Correction are pulled off drug therapy medications and must endure painful withdrawal. Upon release, prisoners may be given a single shot of Vivitrol to block opioid receptors for a month. Because of sweetheart deals with departments of correction and the National Sheriff’s Association, Vivitrol (naltrexone) has become the only treatment currently offered at $1000 a pop in Alaska, Colorado, Kansas, Iowa, Missouri, Louisiana, Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Hamphire, and Massachusetts. There are only a few states and a handful of corrections facilities where a full range of MAT options are being used.

STAT News reports that those without treatment in jail are at extreme risk of overdosing on the “outside” because their tolerance to drugs has dropped and they reenter the world with the same triggers for their drug use. A 2013 study in the Annals of Internal Medicine showed that, in the two weeks after release, former inmates overdose at rates nearly 130 times as high as the general population.

According to an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “opioid agonist therapy with methadone hydrochloride, a full opioid agonist, or buprenorphine hydrochloride, a partial agonist, effectively treats opioid use disorder and reduces mortality.” The JAMA study found “no evidence” that Vivitrol reduced mortality. Despite the advantages of MAT treatment, the JAMA authors lamented, “opioid agonist treatment is used infrequently in correctional facilities. What steps must be taken to change the situation?”

Dionna King, policy coordinator with the Drug Policy Alliance, makes a distinction between MAT and a shot of Vivitrol upon release from prison. Vivitrol blocks the effects of opioids while methadone and buprenorphine eliminate pain, reduce cravings, often improve the health of the patient, and are strongly correlated with continuing drug treatment on the “outside.”

According to Holly Alexandre, medical director of addiction services at SouthCoast Health, medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is a recommended method of opioid treatment used by hospitals, and those with this medical disorder should receive the same care in jail. With MAT, incarcerated people receive drugs like methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone, which ideally are combined with counseling and other therapies.

MAT is considered a corrections “best practice” around the world. The World Health Organization recommends MAT treatment, and a National Institutes of Health review of fourteen MAT studies found only one that did not conclusively demonstrate better post-release participation in community drug treatment programs.

And if Sheriff Hodgson could tear himself away from the microphones and cameras and make the short trip to Providence, Rhode Island, he’d see the advantages of a well-conceived MAT program.

Through an innovative partnership with actual health professionals, Rhode Island’s prisons offer MAT with buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone. The treatment program, which launched in 2016, has resulted in a 61% reduction in post-release overdose deaths. What makes the Rhode Island program so effective, according to Science Daily, is that “the treatment is administered to inmates by […] a nonprofit provider of medications for addiction treatment contracted by RIDOC to provide MAT inside correctional facilities. Upon release, former inmates can continue their treatment without interruption […] in MAT locations around the state. Patients are also assisted with enrolling or re-enrolling in health insurance to make sure they are covered when they return to the community.” Rhode Island’s program is the only one to make the full suite of MAT available to everyone entering or leaving prison. “Medications are continued if they are on them when they arrive and started if they need them upon arrival or prior to release.”

The American Medical Association says it’s unethical to deny opioid agonist treatment to patients. Ross MacDonald, medical director of New York City’s correctional health program, says that every person who enters New York City’s main jail with an opioid addiction problem represents an opportunity for treatment and the possibility of saving a life. The ACLU of Washington State is suing Whatcom County for denying MAT treatment to prisoners with opioid addictions on medical grounds.

Even Donald Trump’s President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis recommends medically-assisted treatment: “Multiple studies have shown that individuals receiving MAT during and after incarceration have lower mortality risk, remain in treatment longer, have fewer positive drug screens, and have lower rates of recidivism than other individuals with [opioid use disorders] that do not receive MAT.”

While the Rhode Island program represents a more level-headed and compassionate approach toward opioid treatment, rehabilitation is still being delivered in the state’s prisons (there are no county jails in the Ocean State). Most of these patients belong in a clinical or rehabilitation setting, not behind bars. Despite this structural defect, Rhode Island is light years ahead of our Bristol County, Massachusetts jail where Sheriff Thomas M. Hodgson starves, abuses, and neglects the medical care and treatment of those who face death by overdose upon release.

Comments are closed.