Gilad Shalit was released today. I posted the following essay more than a year ago. There are still roughly 7,000 Palestinian political prisoners in Israeli jails whose families love them every bit as much as Shalit’s.

Tomorrow, June 25th, 2010, will be the fourth year that Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit has remained in captivity. But it has also been over forty years since Palestinians in greater numbers have been imprisoned – many without ever receiving a trial.

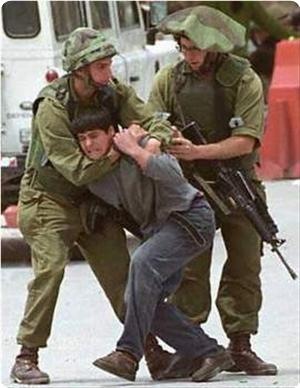

For three generations, more than 20% of all Palestinians – and some estimate half of all Palestinian men – have see the inside of an Israeli prison sometime in their life.

In 2010, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics reported over 7,000 Palestinians being held in Israeli prisons, 264 under administrative detention – indefinite imprisonment without trial.

Adalah, the Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel cites statistics noting that as of March 2010, 6631 Palestinians were imprisoned in Israel, 8 detained under the Illegal Combatants Law (7 of whom are from Gaza) and 237 were administratively detained. 35 were women; 337 were child prisoners, including 39 under the age of 16; and 773 were from Gaza.

The Israeli human rights group B’Tselem detailed civil and human rights abuses in a report titled “Without Trial” and has called for an end to Israel’s illegal detentions: “Under international law, a state may detain a resident of occupied territory without trial to prevent danger only in extremely exceptional cases. Israel, however, holds hundreds of Palestinians for months and years under administrative orders, without prosecuting them. By doing so, it denies them rights to which ordinary detainees in criminal proceedings are entitled: they do not know why they are detained, when they will go free and what evidence exists against them, and are not given an opportunity to refute this evidence.”

Two weeks ago, blogger Richard Silverstein reported that “Yediot Achronot published a story about a Mr. X imprisoned in an Israeli jail. The man was in solitary confinement. His jailers did not know who he was, did not share a word with him, no one came to visit him. No one seemed to know he was there. They didn’t even know what crime he had committed or how he came to be in the prison. His prison cell was completely isolated from other prisoners and he couldn’t communicate in any way with them.” Then the article was pulled from the paper and the story was censored. The story was picked up by the Daily Telegraph in the UK. The prisoner apparently shares the same treatment as Gilad Shalid.

The Israeli Foreign Ministry lists seven Israeli soldiers either kidnapped or missing in action: Staff Sergeants Zecharya Baumel, Zvi Feldman, and Yehuda Katz – all missing since 1982 in a battle at Sultan Yakoub, in Lebanon; Major Ron Arad, who was captured on 16 October 1986, after his aircraft was shot down near Sidon, Lebanon; Guy Hever, who went missing on the southern Golan Heights in August 1997; Majdy Halabi, last seen hitchhiking in Dalyat El Karmel in May 2005; and finally Cpl. Gilad Shalit, who was abducted on June 25, 2006 near Kibbutz Kerem Shalom. Only for Shalit has there been any recent “proof of life” and Hamas acknowledges holding him.

For the last four years 23-year-old Shalit has been held in an undisclosed location and, like Israeli Prisoner X, even Red Cross visits have been denied. Lt. General Gabi Ashkenazi has gone on record that securing the release of Shalit is of the utmost importance to Israel. But Ashkenazi has clashed with the Netanyahu government over the degree of importance. For four years Israel and Hamas have rejected each other’s demands and offers. In 2009 a German-brokered deal collapsed after Hamas rejected additional Israeli requirements that released political prisoners go into exile.

Any father – Israeli, Palestinian, or American – feels the pain that Shalit’s father swallows when he talks about his son. I know I do. I understand Noam and Aviva Shalit’s desperation and frustration with both Hamas and their own government. And it deeply disturbs me that Shalit, who was still a teenager when he was captured, and his family are paying a steep personal price. But so are Palestinian families. The father in me appeals to both sides to settle the prisoner negotiations and let all political prisoners – Palestinians and the one Israeli – free. But neither the Hamas nor Likud and Beteinu extremists have ears for appeals to humanity.

But there is a more pragmatic reason to resolve this issue now.

Israel has announced a relaxation of bans on certain humanitarian imports to Gaza in the wake of the flotilla attack. Flotilla organizers and the Turkish charity whose members were killed on the Mavi Marmara may have been accused of being Al Qaeda and Hamas operatives, but the incident has underscored the fact that Hamas remains in charge in Gaza and it represents governance in the besieged strip. While Israel and Hamas can both fume about Zionist or terrorist “entities,” it becomes clearer by the day: they have to start talking to each other. As diverse as the responses to the flotilla attack have been (suits against Israel in the EU versus an outpouring of Congressional resolutions s

upporting Israel in the US), there are two sides – and they must start talking.

Israel recently denied German development minister Dirk Niebel entry into Gaza. To Israel such visits only serve to legitimize Hamas. While this is somewhat ironic in light of Israel’s campaign against “Israel delegitimizers,” the snub of the German diplomat may also have been meant as a message to the international community to butt out of the Shalit negotiations and that talks with Hamas are off-limits.

Indeed, the issue of Hamas legitimacy has been the major stumbling block. Israel has an official policy of not talking to “terrorists.” Neither Israel, the PA, Egypt, nor the US want to acknowledge Hamas. For all its lofty verbiage, the Obama administration has also kept neocon ideology alive by refusing to talk to enemies. But Europe and the Arab and Muslim worlds are more pragmatic. Despite funding from Iran, the Arab League, Turkey, and the EU are willing to at least talk to Hamas. Hamas’ growing legitimacy has been observed by Americans. The New York Review of Books ran an interesting article on Hamas last year by Nicolas Pelham and Max Rodenbeck. Charlie Rose interviewed Khaled Meshaal in Damascus about a month ago. Pretending that Hamas does not represents 1.5 million people is as senseless as pretending that two Republican senators do not represent Idaho, a state with the same population as Gaza.

Acknowledging both elected governments (Fatah in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza) would force an accommodation with each other. But as long as “Palestinian unity” is a precondition for talks, there will be no peace, no end of hostilities between Israel and Hamas, and no resolution of a prisoner exchange.

But resolving a prisoner exchange – perhaps the simplest first step in restarting peace negotiations – would be in everyone’s interest.

It is in Israel’s interests to build on its gesture of relaxing Gaza imports by demonstrating flexibility it has not shown for some time. Now that Israel has been able to turn this gesture into a minor public relations victory and has indeed relaxed some import items, Shalit becomes slightly less valuable to Hamas as a tool to win import concessions from Israel. For Hamas, Shalit now has value only for a prisoner exchange. This would be a good time for Hamas to make some minimal concessions of its own in regard to Israel’s demands. Similarly, on the anniversary of Shalit’s capture, the Netanyahu government is under increasing pressure to bring him home. It would be a good time for Israel to make some concessions as well.

To both sides: Bring Gilad Shalit home. Bring all the political prisoners home.

Comments are closed.