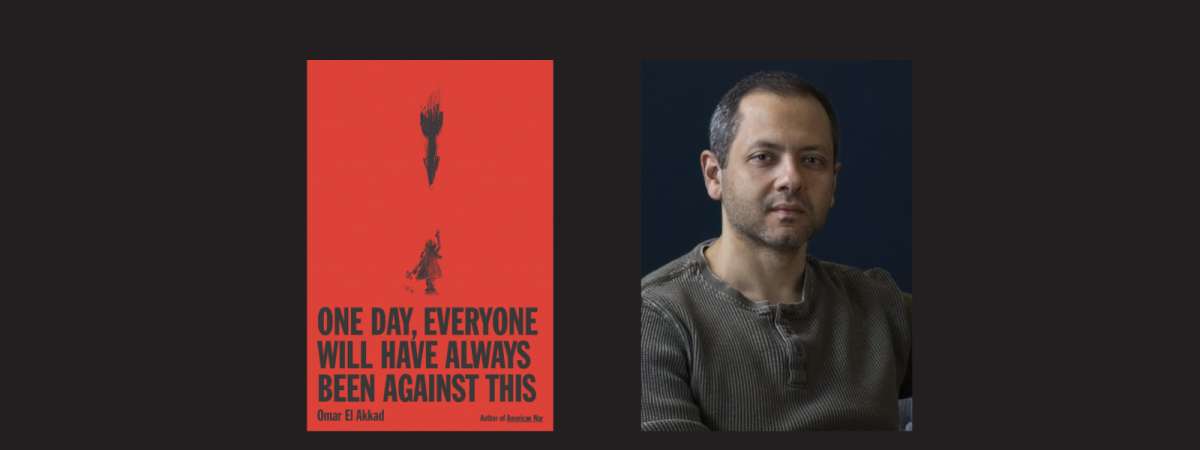

Omar El Akkad's new book "One Day, Everyone Will have Always Been Against This" breaks Western liberalism down to its termite-ridden studs. Straightaway, Akkad introduces his thesis, as well as explaining why so many people have been radicalized by the gauze falling away from their eyes. Or perhaps it's just the contradictions of both capitalism and western liberalism that have never been so glaringly obvious before.

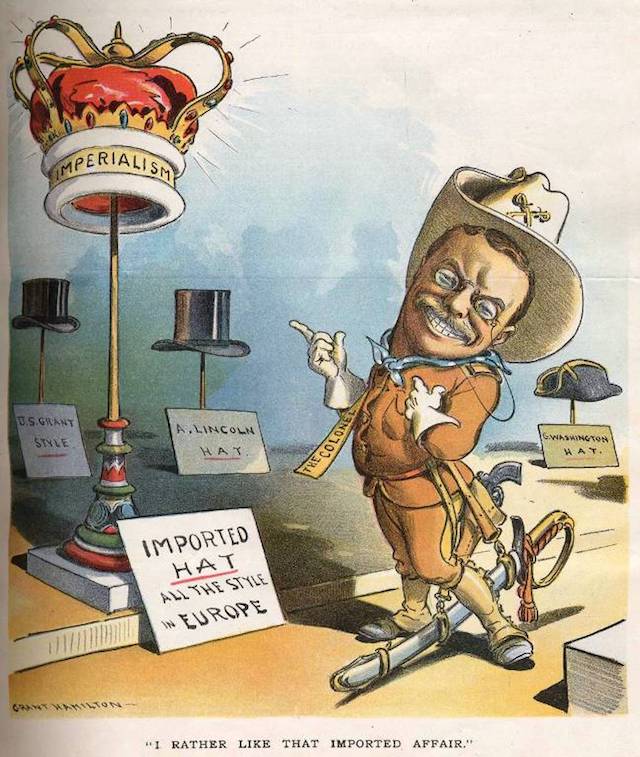

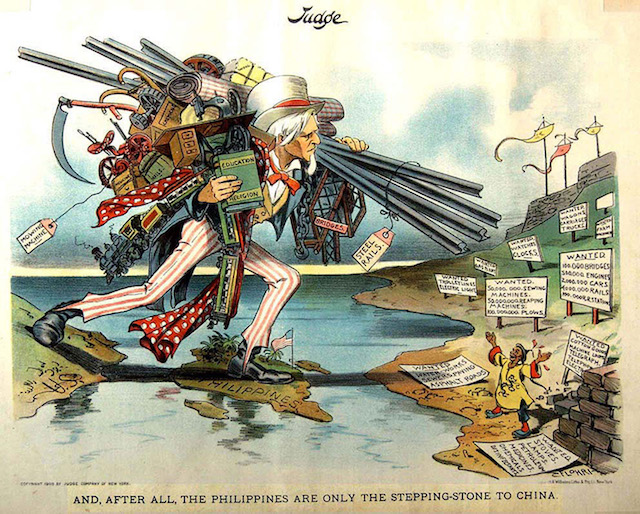

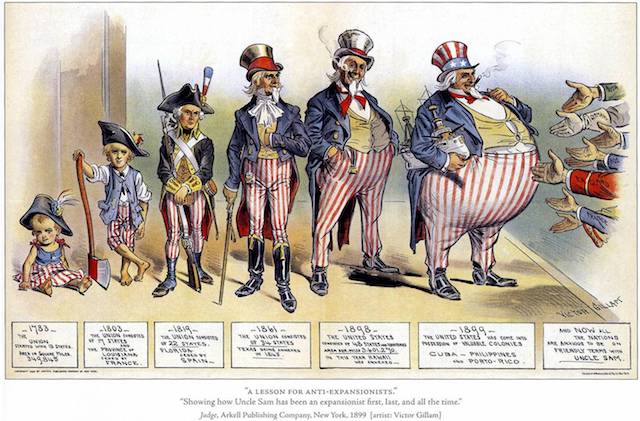

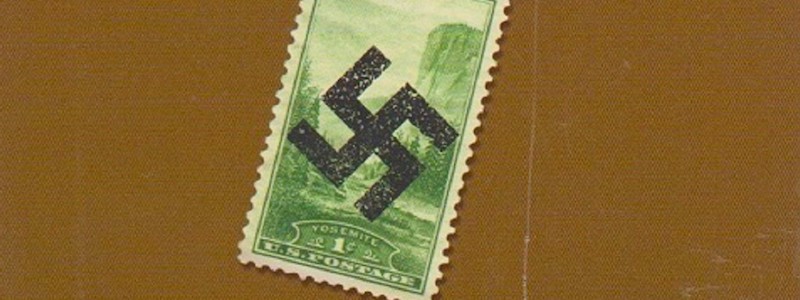

Akkad describes this widespread radicalization as an abrupt "severance" from acceptance of the lies of neoliberalism and neocolonialism. And as an account of the end — actually the West's own abnegation — of its so-called "rules based order." And just as the "rule-based order" is only valued when it serves Western purposes and then is so easily discarded when it's not, Liberalism itself works that way.

This is an account of a fracture, a breaking away from the notion that the polite, Western liberal ever stood for anything at all.

To maintain belief in what is commonly called the rules-based order requires a tolerance for disappointment. It's not enough to subscribe to the idea that there exist certain inflexible principles derived from what in the parlance of America's founding documents might be called self-evident truths, and that the basic price of admission to civilized society is to do whatever is necessary to uphold these principles. One must also believe that, no matter the day-to-day disappointments of political opportunism or corruption or the cavalcade of anesthetizing lies that make up the bulk of most every election campaign, there is something solid holding the whole endeavor together, something greater. For members of every generation, there comes a moment of complete and completely emptying disgust when it is revealed there is only a hollow. A completely malleable thing whose primary use is not the opposition of evil or administration of justice but the preservation of existing power.

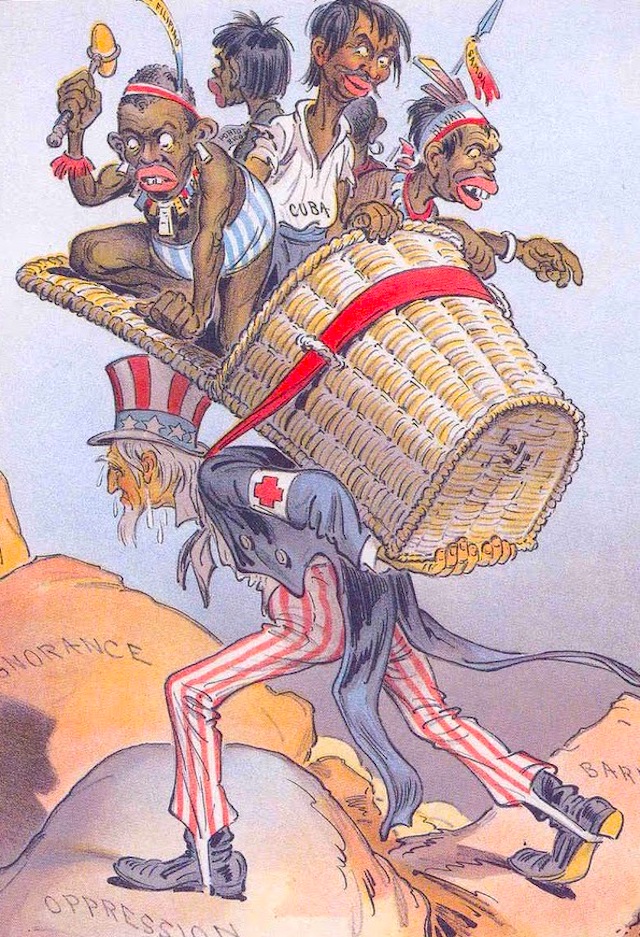

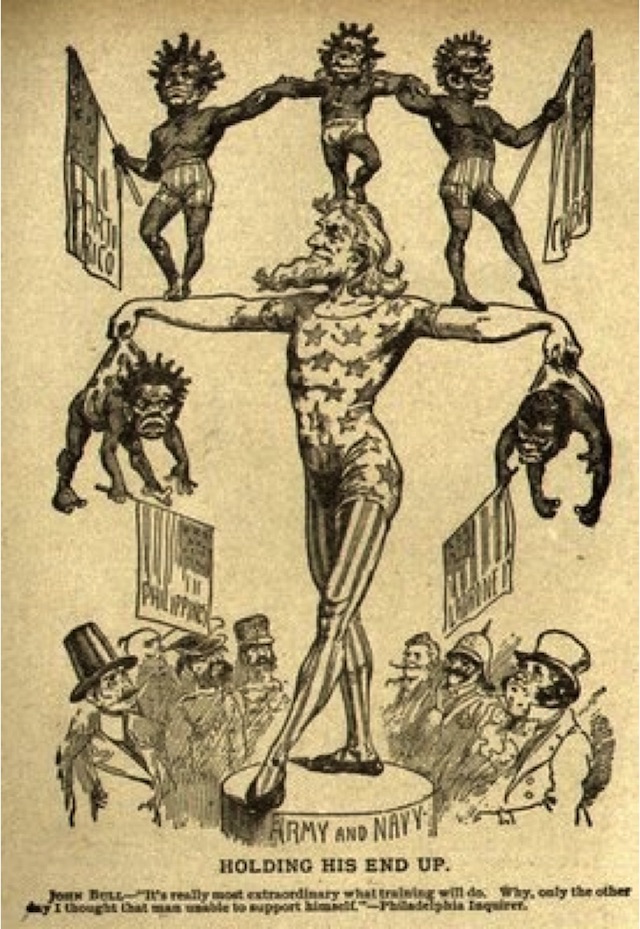

History is a debris field of such moments. They arrive in the form of British and French soldiers to the part of the world I'm from. They come to the Salvadorans and Chileans and Iranians and Vietnamese and Cambodians in the form of toppled governments and coups over oil revenue and villages that had to be burned to the ground to save them from some otherwise terrible fate. They arrived at the turn of the twentieth century to Hawaii (the U.S. apologized for the overthrow of the Hawaiian government-almost a hundred years later). They come to the Indigenous population eradicated to make way for What would become the most powerful nation on earth, and to the Black population forced in chains to build it, severed from home such that, as James Baldwin said, every subsequent generation's search for lineage arrives, inevitably, not at a nation or a community, but a bill of sale. And at every moment of arrival the details and the body count may differ, but in the marrow there is always a commonality: an ambitious, upright, pragmatic voice saying, Just for a moment, for the greater good, cease to believe that this particular group of people, from whose experience we are already so safely distanced, are human.

Now, for a new generation, the same moment arrives. To watch the leader of the most powerful nation on earth endorse and finance a genocide prompts not a passing kind of disgust or anger, but a severance. The empire may claim fear of violence because the fear of violence justifies any measure of violence in return, but this severance is of another kind: a walking away, a noninvolvement with the machinery that would produce, or allow to produce, such horror. What has happened, for all the future bloodshed it will prompt, will be remembered as the moment millions of people looked at the West, the rules-based order, the shell of modern liberalism and the capitalistic thing it serves, and said: I want nothing to do with this.

Here, then, is an account of an ending.

Akkad writes about Western complicity with the genocide in Gaza and the complicity of a liberal press that sugar-coats the reality of empire, preferring to write in the passive voice about its crimes, operating in the service of a liberalism that wraps itself in hollow gestures and performative sentiment, lying to itself about the evil that it actually wreaks, while simultaneously lying to itself about its own inherent (and largely non-existent) virtue.

Beyond the high walls and barbed wire and checkpoints that pen this place, there is the empire. And the empire as well is cocooned inside its own fortress of language — a language through the prism of which buildings are never destroyed but rather spontaneously combust, in which blasts come and go like Chinooks over the mountain, and people are killed as though to be killed is the only natural and rightful ordering of their existence. As though living was the aberration. And this language might protect the empires most bloodthirsty fringe, but the fringe has no use for linguistic malpractice. It is instead the middle, the liberal, well-meaning, easily upset middle, that desperately needs the protection this kind of language provides. Because it is the middle of the empire that must look upon this and say: Yes, this is tragic, but necessary, because the alternative is barbarism. The alternative to the countless killed and maimed and orphaned and left without home without school without hospital and the screaming from under the rubble and the corpses disposed of by vultures and dogs and the days-old babies left to scream and starve, is barbarism.

As an Egyptian-Canadian-American, Akkad is fluent in two languages and two cultures. As a young reporter covering the war in Afghanistan, Akkad quickly discovered the limit of truth-telling permitted to journalists – a limit imposed by Western empire:

It may as well be the case that there exist two entirely different languages for the depiction of violence against victims of empire and victims of empire. Victims of empire, those who belong, those for whom we weep, are murdered, subjected to horror, their killers butchers and terrorists and savages. The rage every one of us should feel whenever an innocent human being is killed, the overwhelming sense that we have failed, collectively, that there is a rot in the way we have chosen to live, is present here, as it should be, as it always should be. Victims of empire aren't murdered, their killers aren't butchers, their killers aren't anything at all. Victims of empire don't die, they simply cease to exist. They burn away like fog.

To watch the descriptions of Palestinian suffering in much of mainstream Western media is to watch language employed for the exact opposite of language's purpose — to watch the unmaking of meaning. When The Guardian runs a headline that reads, "Palestinian Journalist Hit in Head by Bullet During Raid on Terror Suspect's Home," it is not simply a case of hiding behind passive language so as to say as little as possible, and in so doing risk as little criticism as possible. Anyone who works with or has even the slightest respect for language will rage at or poke fun at these tortured, spineless headlines, but they serve a very real purpose. It is a direct line of consequence from buildings that mysteriously collapse and lives that mysteriously end to the well-meaning liberal who, weaned on such framing, can shrug their shoulders and say, Yes, it's all so very sad, but you know, it's all so very complicated.

The slippery ethics of the Liberal confuse and disgust Akkad:

I start to see this more often, as the body count climbs — this malleability of opinion. At a residency on the coast of Oregon, i read the prologue to this book; a couple of days later, one of the other writers decides to strike up a conversation.

"I'm not a Zionist," she says. "But you know, I'm not anti-Zionist either. It's all just so complicated."

I have no idea what to say. I feel like an audience at a dress rehearsal.

There's a convenience to having modular opinions; it's why so many liberal American politicians slip an occasional reference of concern about Palestinian civilians into their statements of unconditional support for Israel. Should the violence become politically burdensome, they can simply expand that part of the statement as necessary, like one of those dinner talbes you lengthen to accomodate more guests than you expected. And it is important, too, that this amoral calculus rise and fall in proportion to the scale of the killing.

Akkad signs a petition to drop charges against anti-genocide protesters at an awards ceremony for the Giller Prize, a Canadian literary event supported by a bank with half a billion dollars of investments in Israel:

The letter sets off a small firestorm of newspaper articles and rival open letters. I suppose it makes sense: people were made momentarily uncomfortable at a black-tie gala — someone has to pay.

Watching footage of the demonstration later, what fascinates me isn't the smattering of boos from the audience as the protesters take to the stage, it isn't even the protest itself — it's all the people in that room, so many of them either involved in or so vocally supportive of literature, who keep their heads down, say nothing, wait for it all to just be done. A room full of storytellers, and so many of them suddenly finding common cause in silence.

I am reminded of this in the Democratic Party response to Trump's non-stop bald-faced lies in his "State of the Union" speech. Only one courageous congressman stood up and shouted out in protest (just as only one courageous congresswoman opposed the rush to war after 911). The rest of the combined houses of Congress passively remained in their seats as America's first openly fascist president declared war on every value Americans have traditionally revered. A group of Democratic women donned pink pants suits, a few Democrats held paddles – paddles! really? — expressing some unmemorable version of "tsk tsk."

This calorie-free performance was typical of American Liberalism. This was one more example of Liberalism's amoral incapacity to take a side and fight for it. This is the manifest poverty of Liberalism. And this is precisely what Akkad's book is all about.