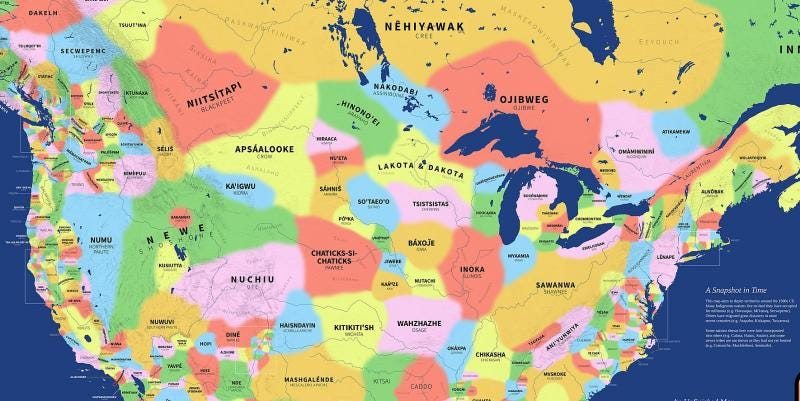

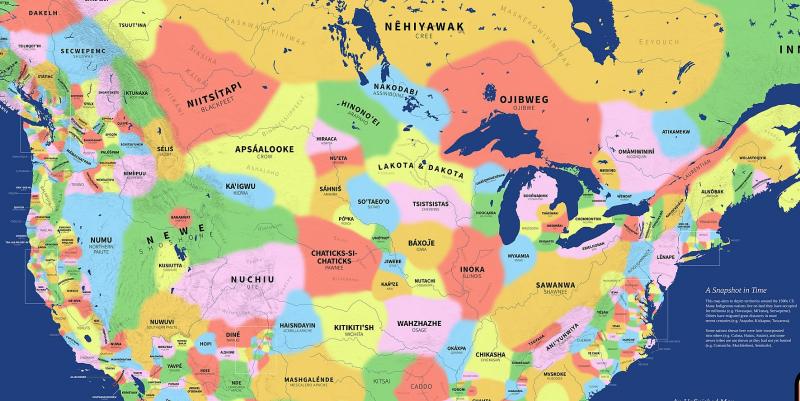

Both slavery and the genocide of Native Americans were committed as soon as colonists began arriving in the Americas. It has taken White America over 400 years to begin a process of self-examination for its crimes — and as a group we’re not accustomed to apology or introspection. As the Town of Dartmouth approaches its 400th anniversary, it is only now looking at two issues related to its depictions of Native Americans. One is historical signage now under review by the Historical Commission. The other is the town’s school mascot, the “Indian.” Jim Hijiya is an emeritus professor of history at UMass Dartmouth, lives in Dartmouth, and offers a thoughtful take on changing the mascot’s name.

by Jim Hijiya

Whether to keep an Indian as a school mascot is a hard question to answer — at least it has been for me. I’ve changed my mind twice already.

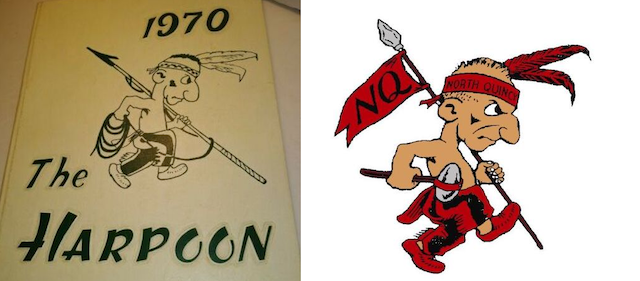

I was born and raised in Spokane, Washington, less than twenty miles down the highway from Eastern Washington State College. My sister went to Eastern in the late 1960s, and I rooted for the sports teams from her school. Those teams were called the Savages, and their logo featured a Native American who did not look friendly.

At the time I didn’t see anything wrong with that. It was what I grew up with. I was used to it, and so was everybody else, except maybe some Indians, and nobody cared what they thought. Go, Savages!

Then I went off to college, followed by graduate school. In the 1970s I heard that Eastern had changed its mascot. They weren’t the Savages anymore; they were now the Eagles. “Eastern Eagles” — kind of poetic.

Some of Eastern’s alumni complained thunderously about the treacherous and spineless abandonment of tradition; but I, having spent a few years away from home, now thought the change made sense. The word savages, when associated with Native Americans, did not reflect kindly on those Natives. It seemed unfair.

However, at about the same time, I heard about other name changes for which I had less sympathy. The Stanford University Indians had switched their name to the Cardinal (singular, with no S, indicating a shade of red, not a flock of birds). On the other side of the continent, the Dartmouth College Indians had changed their name to the Big Green. One red, one green, no Indian.

I thought that this was going too far: political correctness run amok. Sure, Savages was derogatory. Redskins was not much better. But Indians? What’s wrong with that? You insult somebody by calling her or him a “savage,” but there’s nothing wrong with being called an “Indian.”

That’s what I still thought when I came to teach history at Southeastern Massachusetts University in 1978. My neighbors had kids who went to Dartmouth High, so I tagged along with them to football games on Thanksgiving. With untempered enthusiasm I rooted for the Dartmouth Indians.

But then, over the years, I changed my mind again. I read more and thought more and came to a different conclusion.

Indians are a race of human beings, like whites or blacks or Asians or Hispanics. However, I don’t know of any sports team named after whites, blacks, Asians, or Hispanics. “The Orientals”? “The Fighting Caucasians”? I can’t even imagine giving a team a name like that. So why do we have “Indians”?

Then I got to thinking about who gets used as mascots. Most often they’re animals: Atlanta Falcons, Boston Bruins, Chicago Bulls, Detroit Tigers. Sometimes mascots are human beings but ones who aren’t around anymore: USC Trojans, Bishop Stang Spartans, Minnesota Vikings, Pittsburgh Pirates, New Bedford Whalers.

Some mascots are beings that never existed: Giants (from New York or San Francisco) or, closer to home, Blue Devils from Fairhaven. The Boston Celtics and the Fighting Irish of Notre Dame both are represented by leprechauns.

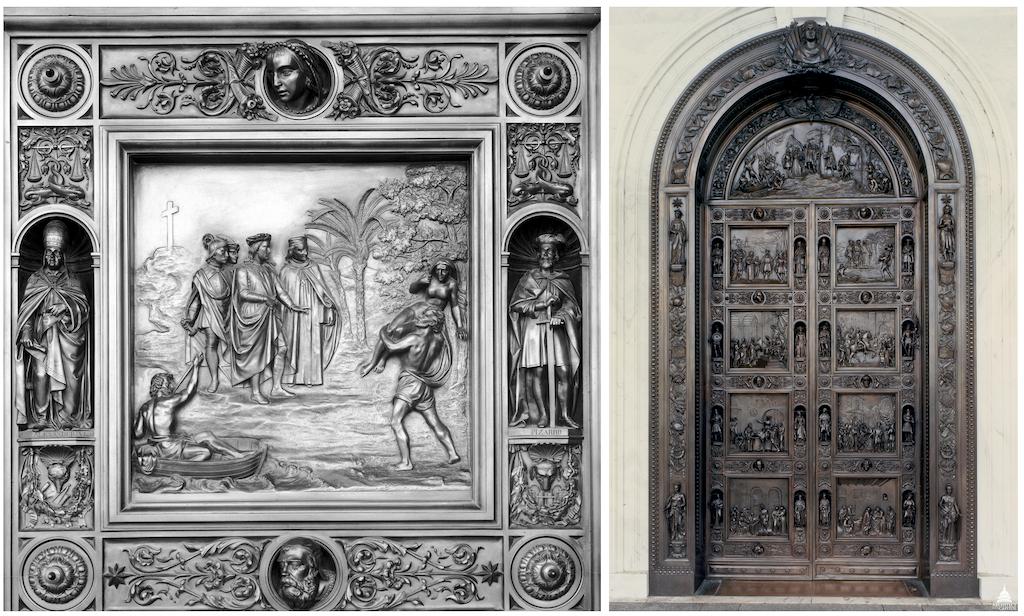

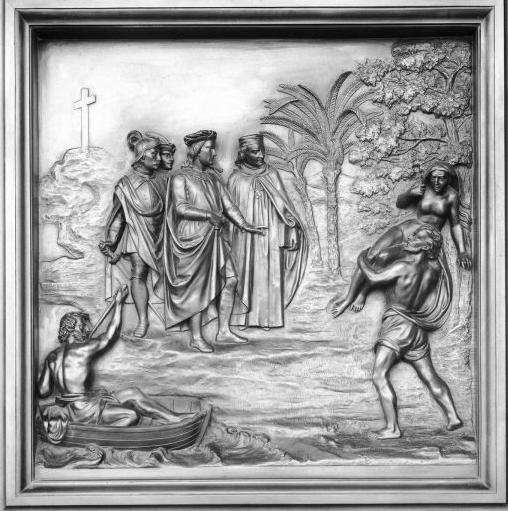

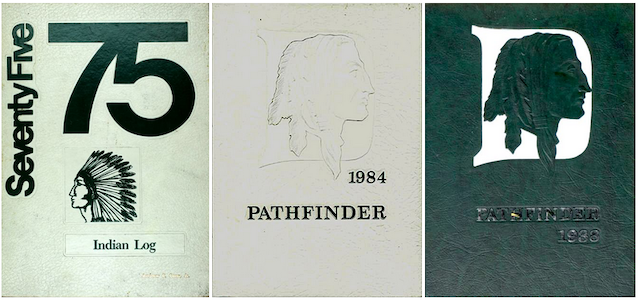

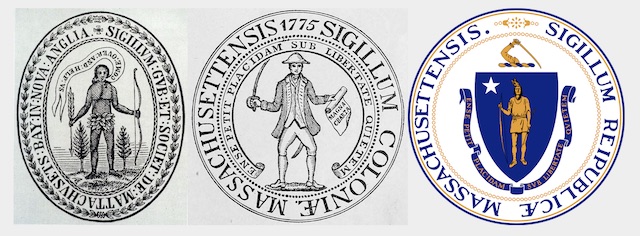

We have, then, three common kinds of mascots: (1) animals, (2) people from vanished civilizations, and (3) creatures of fantasy. At first glance, the Dartmouth Indian may seem to belong to Category 2. He wears paint on his face and feathers in his hair, which not many people do any more, at least not at the office or the supermarket. He seems to belong to the past. The Dartmouth High School Student Handbook says that the mascot recognizes “the Native American Heritage of the South Coast,” and “heritage” comes from the past.

Actual Indians, however, exist abundantly in the present, which causes a problem for Dartmouth High. When your school mascot shares a name with living people, you need to be careful not to make that mascot look bad. The Student Handbook prohibits “dress, gestures and/or any other activities or characterizations that portray the Dartmouth Indians in a stereotypical, negative manner.” For example, students attending games are forbidden to do the Tomahawk Chop, which makes Indians look like bloodthirsty savages.

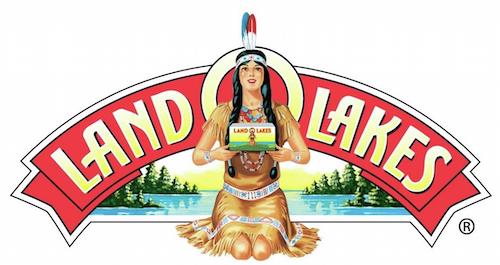

The image of the Dartmouth Indian is not explicitly “negative,” but it is “stereotypical.” It has to be. No one icon can accurately depict a group as numerous and various as Native Americans. The Dartmouth Indian has to stand in place of many people who don’t look much like him: women, for example. (I can’t think of any school mascots who are distinctively female.)

The Dartmouth Indian is a man in the prime of life, and he looks vigorous. Though he lacks armor and armament, he appears to be a worthy adversary for the Bishop Stang Spartan with his helmet or the New Bedford Whaler with his harpoon. This is why he symbolizes the Dartmouth High School sports teams: he embodies physical prowess.

This is also why he does not symbolize the school math team or debate team, who, whatever other strengths they possess, are not distinguished by their athleticism. Those teams don’t call themselves “the Indians.” They call themselves “Dartmouth.”

But why can’t the Dartmouth Indian smile? Why does he look so serious?

Because that’s his job. Like a Lion or a Tiger, he is supposed to scare you. He is the embodiment of a boast, saying, in effect, “I am strong, and I will beat you!” Consider the fact that Pirates, Corsairs, and Raiders are sports mascots. When they roamed the earth as actual people, they were loathed as robbers and murderers; but now that they’re safely deceased, we honor them as symbols of martial dexterity. Even the leprechaun is pugnacious: the Notre Dame mascot has his fists up, spoiling for a fight, and the Boston Celtics symbol has a hand resting on a cudgel. You don’t want to mess with these guys. And you don’t want to mess with the Dartmouth Indian.

But here’s the problem. The Dartmouth Indian exploits and reinforces an old stereotype of the Indian as a killer. He may not be called a “Brave” (like Atlanta) or a “Warrior” (like Golden State), but he sure looks like one, enough so that he makes some fans want to perform the Tomahawk Chop. He makes it easy for us to continue to believe that Indians are all about battle. We remember them mainly for the same reason we remember the Trojans and the Spartans: they fought wars.

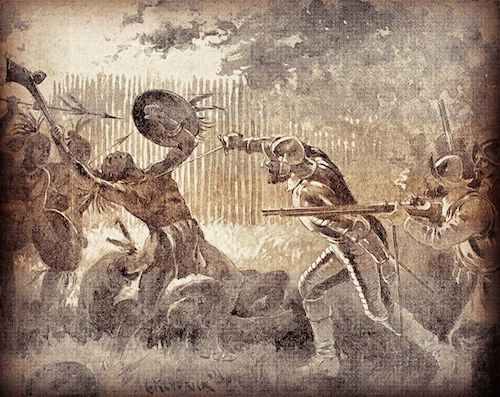

For four hundred years, Indians seemed dangerous to Americans who weren’t Natives. As the whites pushed Natives off the land and subjected them to alien rule, Indians fought back, killed some of the invaders, terrified the rest, and created a lasting image of the Indian as a menace. That image was used to justify exterminating Natives and taking their land. Even after the Indians had been subdued, their threatening image was perpetuated in books and movies. This, then, is why Indians, unlike all the other human races, serve as mascots for athletic teams: because of their reputation for violence.

If the mascot of Dartmouth High sports teams were a Bear or a Viking or a Giant, there would be nothing wrong with his seeming to be a potential threat to public safety. However, he’s not. He’s an Indian. By reminding us that some Indians, sometimes, were fighters, he lets us forget that most Indians, most of the time, devoted themselves to peaceable pursuits like farming or hunting or caring for children — or playing sports.

Try to imagine a different kind of Indian mascot: say, one looking like the picture on the Sacajawea dollar (a coin, by the way, that you never see), which commemorates the guide and interpreter for Lewis and Clark. A woman would be just as typical of Native Americans as the current Dartmouth Indian. However, I don’t think she would be as inspiring to the football team. For that we want somebody rough and tough.

But does it have to be an Indian?

There are, of course, arguments for keeping the high school mascot. For example, some people insist that the Dartmouth Indian honors the original inhabitants of our region. The high school handbook says that the Dartmouth Schools “shall be responsible for educating Dartmouth students on the history and important role that the Apponagansett-Wampanoag” played in the history of Dartmouth, so perhaps the mascot is supposed to be part of a program teaching students about Native Americans.

But does that happen? Maybe at some point in the students’ education a teacher tells them something about the Apponagansetts. If it’s not an integral part of the curriculum, however, I doubt that students remember much. Are there courses for them to take in subjects like Native American History, Conversational Wampanoag, or Indians in Contemporary Society? I don’t think so.

Is there, then, any reason to believe that Dartmouth students know more about Indians than do students at New Bedford High or Bishop Stang? Probably not. What Dartmouth students know about Indians, I suspect, is what they have seen on their uniforms or green sweatshirts. But isn’t that granting “honor” to Indians on the cheap?

Before we make our judgment on the Dartmouth Indian, there is one very important question that we ought to ask: What do actual Indians think? I have read that some local Native people love the mascot (though they might not like having it called a “mascot”) and want to keep it. I can understand that. The Dartmouth Indian is a symbol of courage and strength, somebody who will not be pushed around, somebody to make you proud.

If you wrap yourself in the image of the warrior, however, you trap yourself in that same image. It’s hard to look like a warrior and also look like, say, a novelist or a nurse. Thus the symbol narrows our vision of what Native people are; every stereotype, even a positive one, carries a price tag. By perpetuating the idea that Indians are warriors, we give fans of the Atlanta Braves and Florida State Seminoles a stronger excuse for doing the Tomahawk Chop. Warriors and tomahawks go together.

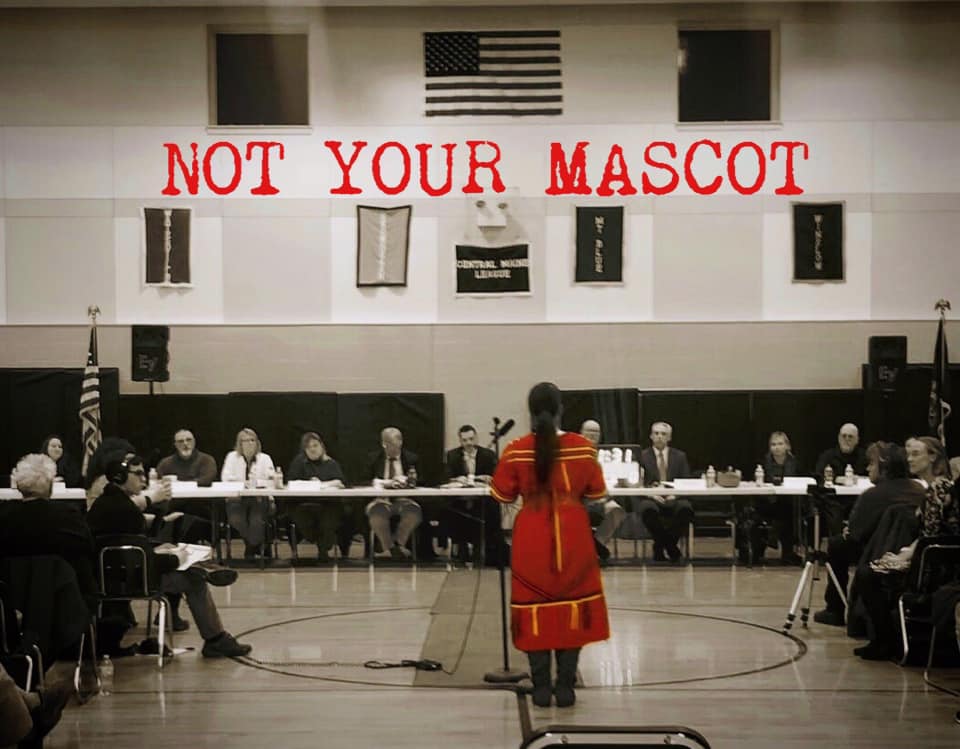

This is probably why I have read about not only Native Americans who want to preserve the Dartmouth Indian but also about ones who want to get rid of Indian mascots altogether. The National Congress of American Indians, for example, has applauded Maine’s recent law banning all Indian mascots at public schools in the state. I don’t know whether the NCAI accurately represents Native opinion, but I suspect that it represents a significant chunk of it.

Now I would like to know what tribal councils and large numbers of individual Indians in southeastern Massachusetts believe. If there is a consensus or even a strong majority opinion among the people most affected by the existence of the Dartmouth Indian, then I think we ought to let their judgment weigh heavily on the scales. I hope that in its consideration of this issue, the Dartmouth School Committee will seek out several organizations and many individuals to find out what Native people want.

I think we all should do a cost/benefit analysis. The benefit of having an Indian as the symbol of Dartmouth sports is obvious: it associates Native Americans with courage and strength. The cost of having an Indian mascot, in contrast, is not obvious but hidden: you can’t see its effect right away, and you have to think about it before you can see it coming. Associating Indians with physical struggle perpetuates the notion that fighting is what Indians are all about. I think there’s more to them than that.

I can understand why many Dartmouth High School alumni don’t want to give up the Indian. He was part of their high school experience, they cherish that experience, and so they cherish the Indian. What I hope they realize now, however, is that he was not an essential part of that experience. If the mascot had been an Eagle or a Pirate, the students’ lives at Dartmouth High would have been pretty much the same. They would have learned math and history (or not), enjoyed the football and basketball games (or not). The mascot doesn’t make much difference. It’s the school itself that counts.

If Dartmouth High gets a new mascot, people will get used to it, though it may take a generation or two for everybody to come around. At Eastern Washington University nowadays, students cheer wholeheartedly for the Eagles. A few still wish the Savages were back on the warpath, but not many. A nephew of mine graduated from Stanford a year ago, and he didn’t even know that his university’s teams had once been called the Indians instead of the Cardinal.

How soon we forget. And how fortunately.